Limited Miniseries

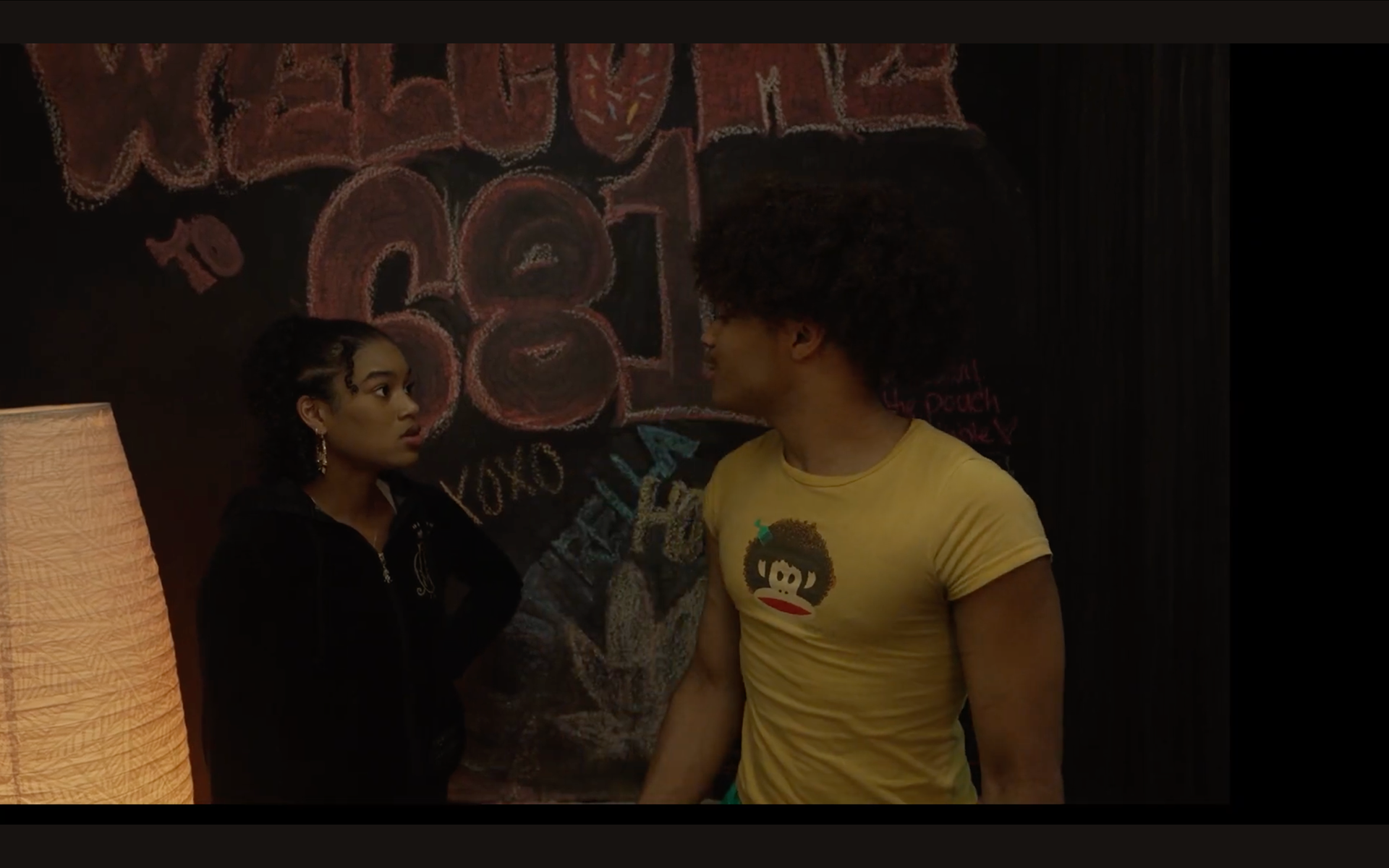

As the showrunner for this limited miniseries, I have taken on a multifaceted role to bring this project to life. My responsibilities span across writing, acting, producing, and directing select episodes, making it essential for me to curate the narrative and ensure a cohesive vision.

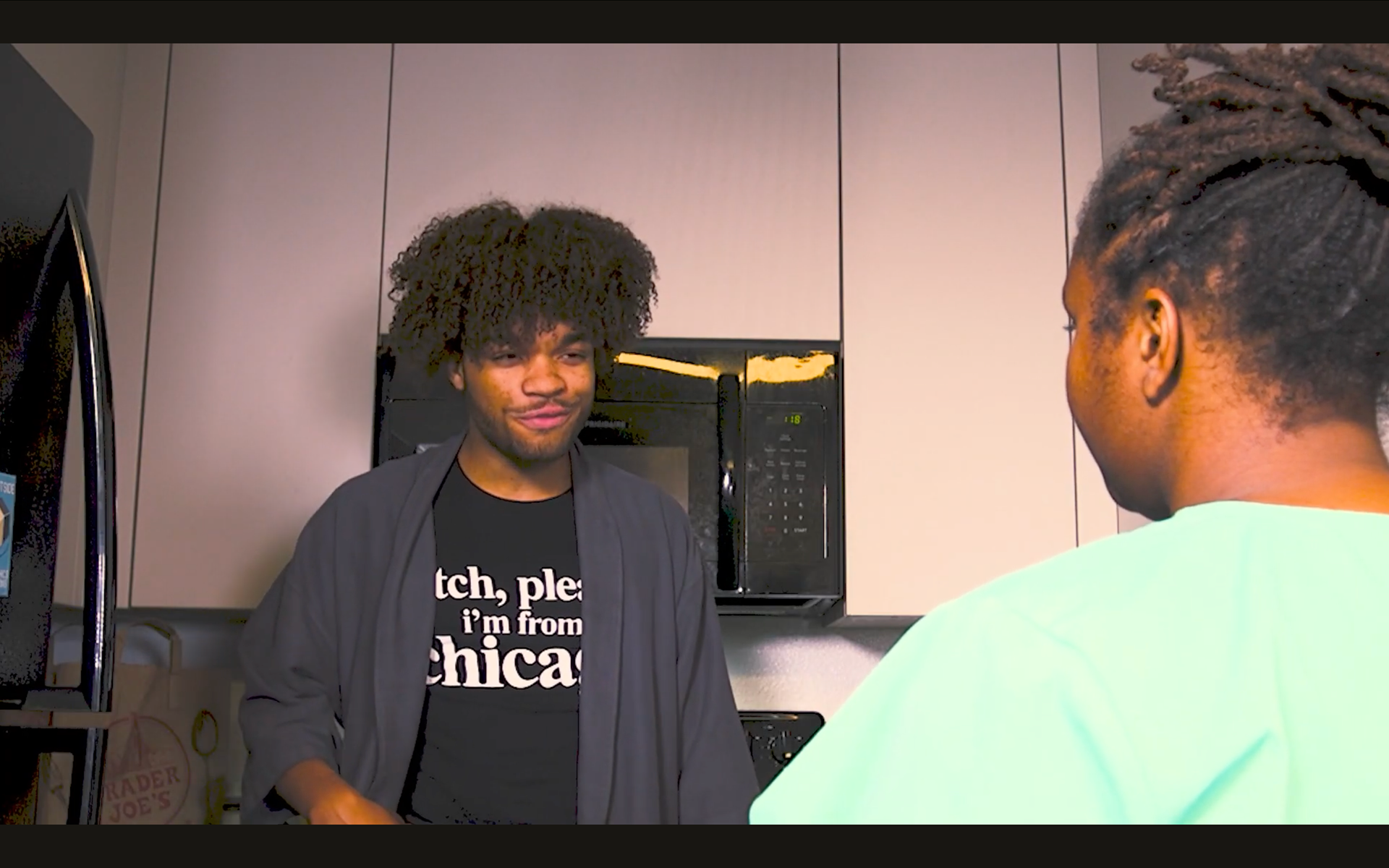

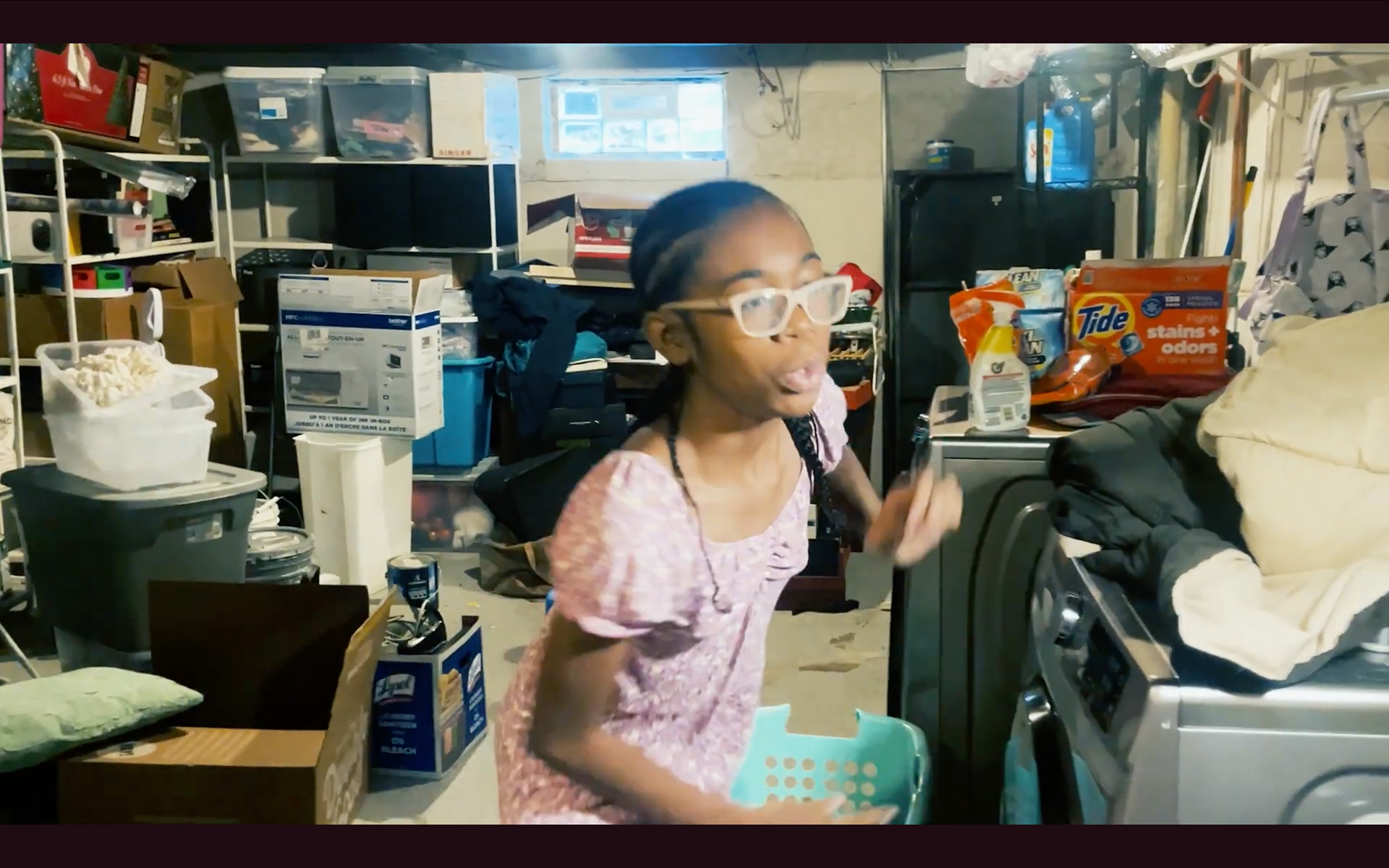

This project is more than just a traditional miniseries; it’s designed with accessibility at its core. The series lives both as a miniseries and on an Instagram channel, where I’ve intentionally employed various mediums to offer a broader, more nuanced story. I am particularly focused on the figurative use of these mediums, integrating principles like the defense of the poor image to challenge traditional production values, and using the concept of the bottle episode to creatively navigate constraints such as budget, time, and experience.

My involvement extends to every stage of production, from pre-production to post-production, as well as overseeing digital media aspects to ensure the series resonates with its audience. This work is deeply personal and reflective of my commitment to storytelling, and it’s set to be released shortly.

Too often in this field, filmmakers—especially independent ones—don’t have access to the art form in its fullest expression.

The industry prioritizes profit, power, and monopoly. The same people get the same roles, the same chances, the same support. And serial narratives? They demand not only creativity, but endurance—a long, strategic vision that’s difficult to maintain when you’re working with real-world constraints.

Budget. Materials. People’s time. Consistent dedication. Even experience—or lack of access to gain it—can become a barrier.

Still, we do it.

We build worlds out of scraps and seconds, pulling together what we have to tell stories that deserve to be seen.

It’s an honor and a blessing to chase this path—to be a filmmaker not because the platform was handed to me, but because I dared to build one of my own.

What Does It Mean to Be a “Student Film”?

Student films are typically low-budget works created within academic programs, intended to teach hands-on filmmaking. Often made with limited resources and inexperienced crews, they carry a unique blend of experimentation and constraint. But the term “student film” does more than describe origin—it shapes how audiences interpret the work.

The audience often overlooks that these films are not just assignments, but launchpads—spaces where the next generation of filmmakers take early creative risks. They may see the rough edges, the lighting flaws, or uneven performances, and attribute them to a lack of professionalism. What they don’t always see is the intention—the conceptual rigor, emotional labor, and strategic innovation being honed behind the camera.

Here’s what defines the medium more deeply:

Purpose: Beyond teaching technical skills like directing, cinematography, and editing, student films are about learning how to think cinematically. They test out ideas that may not be commercially viable, but culturally or personally necessary.

Budget and Cast: Working with ultra-low budgets and volunteer actors (often compensated through TFP models), student filmmakers stretch every dollar, every moment, and every collaborator’s time. It’s not just about making a film—it’s about learning to produce under pressure.

The “Student Film” Aesthetic: There’s a rawness that some call “amateur”—but that rawness is also a kind of honesty. These films often carry emotional stakes and experiment with form in ways that would be edited out of a commercial project.

Professional Development: These projects often serve as the first entries on a résumé, demo reel, or portfolio. They’re stepping stones, but also standalone works of art with their own merit.

Legal + Union Status: Many are covered by university insurance and often operate under non-union conditions. But even here, student films can be a gateway for working with SAG-AFTRA under special agreements, offering early-career actors and filmmakers access to professional networks.

In a world where polish often overshadows process, student films remind us that every master was once a beginner—and that the future of cinema is often being workshopped quietly in a classroom, a dorm room, or a campus editing suite.

We should list things like how many hours of production 100 how many crewmembers with no experience 7 how many crewmembers with experience 3 how much budget 150 was provided how many meals we made in the kitchen 8. How many meals were purchased 5. How many actors and key crew we had graduate in the middle of shooting a student serial Webseries 4.

What does it mean to make accessible art? In a media landscape driven by pristine visuals and exclusive distribution, accessible art dares to circulate beyond elite platforms and glossy presentations. Hito Steyerl’s Defense of the Poor Image reminds us that low-resolution, widely shared media can carry just as much — if not more — emotional, political, and cultural weight as its high-res counterpart. By embracing the “poor image,” artists resist capitalist gatekeeping and allow their work to move freely, finding people where they are — on phones, in classrooms, across borders. In this way, accessibility isn’t just about reach; it’s about intent, ethics, and disrupting systems of control.